The Finest LCS

![]()

OFFSEASON REPORT by Gary Jacobs

The Finest LCS

|

|

|

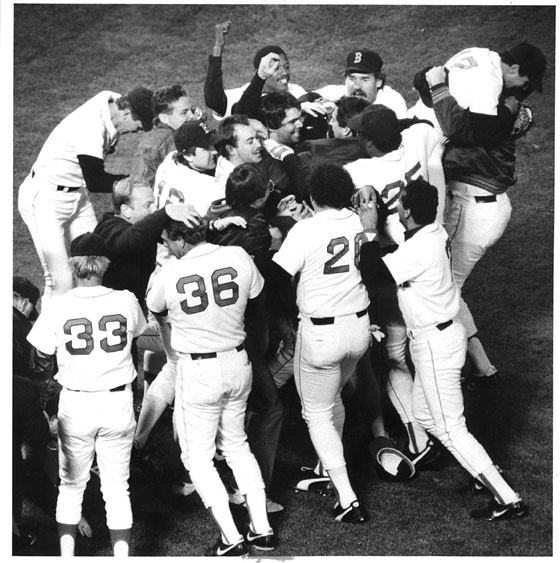

(Boston Globe File Photo) |

OCT. 19, 2006 -- It was a pulse-pounding, amazing, improbable comeback, wasn’t it? It had a little bit of everything: clutch performances from players who failed to impress during the regular season; stars overcoming injury; timely late-inning home runs; a lucky bounce or two; a ninth inning where the Sox, backs against the wall, dismantled the other guy’s lights-out closer; and when it was all said and done, the Red Sox would come together at the mound in a joyous throng and celebrate having won the American League Pennant. It would go down as the greatest comeback in Red Sox' history.

2004? Nope. Try 1986.

Before The Idiots, before John Henry and Larry Lucchino and Theo Epstein, before Dan Duquette, before The Curse, even before “25 men, 25 cabs,” there were John McNamara’s 1986 Red Sox, who overcame a 3-1 deficit in the ALCS – and a 5-2 deficit in the ninth inning of Game 5 – to the then-California Angels for the right to represent the American League in the World Series.

We all know what came 12 days later: defeat as humbling and draining as can possibly happen in the world of sports. Any self-respecting Red Sox fan felt a duty to obliterate the memory of that crushing season from his memory.

But if, instead of spitting the bit in epic, tragic fashion, the Red Sox had been able to close the deal 20 years ago, children from Springfield to Salem would be schooled in the magical summer of 1986, and its just as magical autumn, whose climax came not in the World Series, but the week before in the LCS, just as in 2004.

And now that 2004 has come and gone, bringing with it redemption and neutralization of all the bitterness of past years, the story of the 1986 ALCS deserves - needs – to be told, needs to find a new audience 20 years after the fact, to acknowledge heroic deeds and to remember just how close the Red Sox came to bowing out of the playoffs without even a chance at glory.

* * *

The 1985 edition of the Boston Red Sox defined mediocrity; they finished a perfect 81-81, 18 ½ games behind AL East leading Toronto, good for fifth place in the seven-team division. With an average attendance of 22,057 (which meant there were around 12,000 empty seats in the park every day), it’s safe to say that Red Sox fever was not exactly running wild in the streets of Boston. Though there were some exemplary individual performances – Wade Boggs won the batting title with a .368 BA, and Dwight Evans won yet another Gold Glove – expectations for the ’86 squad were low.

Indeed, the 1986 campaign promised to show little difference from the previous year. The team made few wholesale changes; the only really big move came in November of 1985, when the team worked a multi-player trade with the New York Mets, which distilled into the Sox sending Bob Ojeda and receiving Calvin Schiraldi and Wes Gardner. A few minor trades and some tentative dips in the free agency pool later (Mark Clear to the Brewers for Ed Romero, for example) and the team was done tinkering. Of the nine starters of the ’85 squad, all but one played the majority of the ’86 season (Romero, replacing Jackie Gutierrez at short, was the only new face on the starting nine).

One big difference was the emergence of future Hall-of-Famer Roger Clemens. In 1985, he missed most of the season with a shoulder injury. It’s difficult to conceive of it today, but by opening day 1986, few of baseball’s cognoscenti knew what Clemens would be able to bring to the Red Sox – especially given his poor spring training performance that year (he finished the vernal tune-up with an ERA over 10). He was fourth on the depth chart behind Hurst, Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd, and Al Nipper.

It was Clemens’ transcendent performance against the Seattle Mariners on April 29 that provided the first clue that 1986 might be a special year. In front of a now-inconceivably small crowd of 13,414, Clemens toed the rubber and proceeded to strike out 20 of the 30 batters he’d face, setting a major-league record.

In a town where the Celtics were still a juggernaut – on their way to winning yet another NBA championship and occupying the hearts and minds of the casual fan, Clemens and his otherworldly performance sent a thrill up the spine of Red Sox fans everywhere. Indeed it apparently did wonders for the Red Sox as well; before that game started their record stood at 8-8. They finished their home stand 6-2, went on an eight-game west coast trip, also going 6-2, and came back winning another home stand, 5-1. By May 21 their record stood at 26-13, good for a .667 winning percentage and a well-established lead in the AL East, one which they wouldn’t relinquish for the remainder of the season.

By October 5, 1986, despite dropping all four games of their final series with the second-place Yankees, the Red Sox closed the season with a 95-66 record, outpacing their closest competition by 5 ½ games. Clemens would finish with a 24-4 record and a 2.48 ERA. For the first time since 1975, the Red Sox were going to the postseason.

* * *

By midseason, it was apparent to then-GM Lou Gorman that the Sox were careening towards a date with October baseball. He made a few trades near the deadline to help push the Sox over the edge. One trade of note was Steve Lyons to the White Sox straight-up for Tom Seaver. Seaver, on the tail end of his Hall of Fame career, was brought in to provide insurance for an injured starter. Ironically, Seaver himself would fall to injury and not be a factor in the postseason.

Another deadline trade they made was with the Seattle Mariners, when the Sox traded Mike Trujillo, Ray Quinones, Mike Brown, and John Christensen (and cash) for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen. Henderson, a burly outfielder/DH type who to that point had never hit more than 17 home runs in a season (1983 for Seattle) nor hit more than .280 (’84, Seattle) was brought in to platoon with Tony Armas, who had won the job with Lyons’ departure, in center.

So with an outfield of Jim Rice, Evans, and Armas, Boggs at third, Romero at short, Marty Barrett at second, Bill Buckner at first, Rich Gedman catching, and burly Don Baylor as the designated hitter, the Sox proclaimed themselves ready for Gene Mauch’s a Angels, who had won the AL West by five games over their closest competitors, the Texas Rangers.

Game one of the LCS, the first postseason game at Fenway Park since Game 6 of the 1975 World Series, took place October 7, 1986. Roger Clemens had more than earned his spot at the top of the postseason rotation. He was countered by the Angels ace Mike Witt. Witt went 18-10 with a 2.84 ERA for the Angels in the regular season.

Scoreless through one, the Angels plated four runs after Clemens had gotten the first two batters out (both by strikeout) in the second. In what appeared to be a mental lapse – or a case of the yips – he walked Bob Boone and Gary Pettis, the eighth and ninth batters in the lineup. A Rupert Jones single, a Wally Joyner double, and a Brian Downing single scored four runs in the blink of an eye and the game was over from that point on. Clemens would go 7.1 innings for the Sox and give up seven earned runs. The Angels won the game in a landslide, 8-1.

Game 2, a match-up between Hurst and Kirk McCaskill, started promisingly. Wade Boggs led off the game with a scorching triple off The Wall that bounced over the head of center fielder Pettis. Marty Barrett doubled to score the run, and the Sox had the first lead of the playoff series. The Sox would score again in the second; the Angels would score once in the third and again in the fourth to tie the score. In the fifth Buckner singled and scored the eventual game winner. Three insurance runs in the seventh (helped along by an amazing three errors by the Angels) and eighth innings made the score a lopsided 9-2 in favor of the Red Sox. The series was tied at one, with each side having blown the other out once.

After a one-day break to travel to the West Coast, the series picked back up with “Oil Can” Boyd. Boyd pitched well but hung two pitches to Dick Schofield and Pettis, both of which resulted in home runs. Boyd pitched well but not well enough, as the Angels took the game 5-3, despite a bizarre reversed call in the fourth inning. Larry Whiteside, writing for the Boston Globe, remembers it this way:

"With two out and runners on first and second, Doug DeCinces hit a slow roller to first that started foul and suddenly kicked fair. It hit the bag and bounced far enough away for Wally Joyner, who had broken up Boyd's no-hit bid, to attempt to score. Boyd scooped up the ball as it caromed off first and got it to Bill Buckner. Buckner threw home, where catcher Rich Gedman put a tag on Joyner. But was it before or after Joyner touched the plate? Terry Cooney was up the line and out of position. He didn't see the tag and called Joyner safe. Boyd and the Red Sox saw the tag, and it was all that Gedman and umpire Nick Bremigan could do to keep Boyd in the game, even after Cooney checked with third base umpire Rich Garcia and reversed the call."

" 'Gedman did tag me,' said Joyner. 'But I had landed on his foot and the plate before he did. I didn't even know what the argument was. I figured the Red Sox were trying to get the umpires to change things to their way, which they did.' "

The reversed call – a rare bit of karma that rolled Boston’s way – was not sufficient for the Sox to reverse their fortunes. The Can took the loss. Boston now trailed two games to one.

Game 4, with Clemens back on the mound and dealing, presented a perfect opportunity for the Sox to tie the series at two games apiece. The game was in Boston’s pocket – they enjoyed a 3-0 lead heading into the ninth inning. Clemens was just about unhittable through eight. Buckner’s two-out double in the sixth plated the first Sox run, with Barrett scoring Spike Owen in the eighth for the 2-0 lead, and Bobby Grich misplayed a tailor-made grounder to second for the third run. The Angels needed to score a lot in a fast hurry if they were going to win.

Well, they did. Doug DeCinces led the inning off with a home run to score the first run. George Hendrick, two-time All-Star OF/1B, grounded to third for the first out. Schofield and Boone singled to put the go-ahead run at the plate, and McNamara had seen enough. He yanked Clemens and put in Schiraldi, who promptly gave up a double to Pettis, bringing in Schofield and narrowing the lead to 3-2 with men on second and third with one out.

McNamara decided to walk Jones intentionally to load the bases. After a by Grich strikeout it seemed as if the strategy might pay off. Except that Schiraldi plunked Brian Downing, which forced in the tying run. It was now 3-1, Angels, and a decided shift in momentum towards the home team.

In the 11th, Grich singled off Schiraldi, scoring Jerry Narron, who had singled in his only at-bat of the game, and the Angels stunned the Sox by taking the game, 4-3, and a commanding 3-1 series lead.

The Angels had a seeming stranglehold on the pennant and their ace, Mike Witt, was scheduled to pitch game five. Schiraldi was pilloried for what appeared to be a choke job for the ages.

The Sox were down to their last game, dispirited and downcast, faced with the prospect of having to win their next three games in a row against an Angels' staff on full rest.

* * *

The fateful game actually started off well for the visiting Red Sox. Rice singled to lead off the inning. After Baylor and Dwight Evans struck out, Gedman homered to give the Sox a 2-0 lead in the second inning.

In the third, Boone sent a solo shot over the wall to bring the Angels to within one. And that would be the scoring until the sixth inning, when one of the most bizarre plays in LCS history took place. With DeCinces on second base thanks to his double to right field and two out, Grich launched a long fly ball to center field. Henderson had it in his glove for the third out, but the baseball gods had other ideas. It popped out of his glove and over the fence for an unlikely two-run home run to give the Angels the lead, 3-2.

In the seventh inning, McNamara lifted Hurst for Bob Stanley. A single, sac bunt, a walk, a double, an intentional walk and a sac fly all contributed to two more runs. The Sox were staring elimination down the throat, trailing 5-2 heading into the eighth inning.

A promising start to the eighth (pinch-hitter Mike “Gator” Greenwell singling up the middle to lead off) was erased when Boggs grounded into a double-play. A Barrett popup later and the Sox were down to their last shot.

After an uneventful Angels eighth inning, the Red Sox were playing what 64,223 Angels fans hoped to be the last three outs of their season. In the locker room, the Angels lockers were covered with plastic sheeting to protect them from the spray of champagne that was all but inevitable. Witt was in his element, having pitched eight strong innings with no signs of letup.

Thus facing elimination, Bill Buckner stepped creakily to the plate (it was said of Buckner that, while some players expressed a hotel room preference in terms of being close to a fire escape, on the first floor, or having a view, Buckner’s preference was to have the room nearest the ice machine to soothe his perennially aching knees). He greeted Witt with a single up the middle. After Jim Rice was called out on strikes for the first out of the inning, Baylor stepped up to the plate.

Baylor was traded to the Red Sox from the Yankees, in exchange for Mike Easler. Neither George Steinbrenner who thought Baylor was well past his prime nor Baylor himself, who hated playing for Steinbrenner (“It's tough enough facing a hard-throwing right-hander without worrying about an owner saying you couldn't hit right-handers”), regretted the move.

With Buckner at first, Baylor took the right-hander Witt, who earlier in his career threw only the 11th perfect game in MLB history, out of the park to close the gap to 5-4.

It was a huge step for the Sox but they still faced the reality of being down by a run in the ninth inning with the bases empty and one out. When Evans popped up to third, it became official; the Sox were down to their last out.

Mauch pulled Witt for reliever Gary Lucas. It was an odd move; their closer Donnie Moore was reasonably well-rested for a closer of the time, having pitched two innings two days previously. Odd move or no, Lucas came in and hit Gedman to put the winning run at first. Mauch had apparently seen enough of Lucas and brought in Moore. John McNamara pinch hit Henderson for Armas.

Henderson was a disappointment through most of the season; he hit for neither average nor power, hitting just .196 with one HR during the regular season. But that’s just the regular season.

He worked the count to 2-2. The Sox were down to their last strike.

After fouling off one pitch, he deposited Moore’s next offering over the left field fence for the second two-run homer of the inning, to rescue the Sox from the brink of elimination in spectacular fashion and give them a 6-5 lead going in to the ninth. A ghostly silence fell over Anaheim Stadium.

But Anaheim would not submit quietly. Brian Downing’s sacrifice fly tied the score at seven in their half of the ninth, but reliever Steve “Shag” Crawford would work his way out of a one-out bases loaded jam to send the game to extra innings.

In the 11th inning, Baylor led off by getting plunked – a specialty of his; he set the modern (post-1900) record for most times hit by a pitch – and Gedman’s sac bunt attempt was so good that he too ended up safe at first with Baylor taking third. Henderson, hero of the ninth inning, once again got the job done with a sacrifice fly to deep center field, scoring Baylor and giving the Sox the lead once again.

This time the Angels would have no answer. With Game 4 goat Calvin Schiraldi on the mound, Rob Wilfong and Schofield struck out and Downing popped up meekly to first-base in foul territory. The Red Sox, one strike away from going home, emerged victorious over the Angels 7-6 after 11 draining innings.

There were two more games to play to determine who would represent the American League in the World Series, but the outcome at this point was foregone. The Sox took more than just this one game; they also took the fight right out of the Angels.

* * *

EPILOGUE

Just like a Hollywood script, the Angels submitted meekly to the Red Sox in Games 6 and 7. Game 6 was over in the third, when Boston, now home for the remainder of the series, put up a five-spot on McCaskill and chased him out of the game. The final score of 10-4 was less lopsided than Game 7, which was won by Clemens and the Red Sox, 8-1. The storybook comeback was complete.

Sort of.

Boston fans, of course, derived little satisfaction out of what was undeniably the greatest comeback in Sox history to date; they were hoisted on their own petard in the World Series, a trauma that cut so deep that the magical events of the previous series lay all but forgotten.

Angels fans saw the ruination of their closer, Moore. Whether from old age (he was 33) or from the trauma of that loss, Moore’s skills fell into sharp decline. Two years later the Angels released him. In June of 1989 the Royals, who had signed him to a minor-league contract, also released him outright, thus closing his 14-year career.

That July 18, Moore shot his wife Tonya in front of his children and then turned the gun on himself. Tonya would survive; Donnie would not. Moore was 35.

The Angels would not return to the postseason until 2002, winning the LCS against the New York Yankees and winning the first World Series in their history against the San Francisco Giants.

The Red Sox would contest for the LCS in 1988, 1990, 1999, and 2003, but each time the Sox would find themselves on the wrong side of victory. Then, in 2004, the world finally finished turning upside-down—and the Red Sox would participate in their first World Series since 1986, winning for the first time since 1918.

The 2004 ALCS supplanted the 1986 ALCS as the biggest comeback in team history. This time fans will be able to savor that delirious win for years to come.

Gary Jacobs, BDD contributor, can be reached at [email protected]