The Most Fascinating Person of 2004

Tune in Wednesday night at 9:00pm on ABC

In the meantime, we've got this most fascinating piece from Baseball Prospectus' Will Carroll

I was fortunate enough to cover the playoffs from a Red Sox perspective on Will Carroll's Baseball Prospectus radio show this past fall. Will was asked to write a 'season in review' piece on Schilling for an upcoming book on the Sox that he and the rest of the BP crew are currently working on. This is something that Sox fans will really enjoy. The following is an exclusive excerpt on Curt Schilling, who called it a "very, very well done piece."

Curt Schilling: Rockin’ One Leg

The base of most championship teams is often their starting

pitching. The Boston Red Sox are no different in this. Peter Gammons said, “The

curse was broken by pitching.” Basing a team on a pitcher with an unstable base?

Now that’s a bit more rare. Years from now, when the legend of the 2004 Red Sox

is told, Curt Schilling’s ankle will be the centerpiece. Limping out to the

mound and mowing down the powerful Yankees in Game Six of the ALCS, stitched

together like some fastball Frankenstein, Schilling has gone from mere man to

baseball myth.

|

|

|

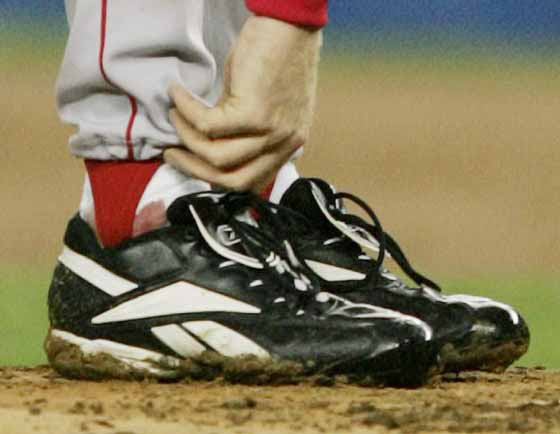

(Boston Globe Photo / Barry Chin) |

The myth is often more interesting than the truth, but in rare

cases, the truth is better than the layers of fiction laid on later. From the

glow of a computer screen on Thanksgiving weekend to the afterglow of a World

Series win, Curt Schilling’s 2004 season is the type of story that Ring Lardner

wrote best...

Schilling was brought in to pair with Pedro Martinez to do one

thing: win the World Series. Recent Series winners have been able to win using

only two dominant power pitchers and a short bullpen. Schilling’s own 2001

Diamondbacks team, pairing him with Randy Johnson, is the prototype for this in

the modern era, though the pattern works throughout the post-1920 era. It was no

sabermetric secret that power pitching wins in the playoffs.

At 6’5, 235, Schilling has the classic power pitcher’s body. He

is thick, not fat. He is tall, but not rangy. He also has the classic power

pitcher’s repertoire, a 92-93 mph fastball that tails slightly. He can run the

pitch up to 96 on occasion when needed, but it isn’t a strikeout pitch. It tends

to get popped up, perhaps due to the changed trajectory of the faster pitch.

Schilling also uses a split-fingered fastball, a pitch that looks like a

fastball, but drops drastically as it nears the strike zone. He also has a

curveball that shows up about twice a game. It’s an average pitch and he doesn’t

control it well.

Like Roger Clemens, Schilling’s power starts in his legs and

thick mid-section. According to studies done by the American Sports Medicine

Institute, reductions in the force generated at the legs translates almost

directly into a reduction in pitch velocity. Add in that Schilling has had

shoulder surgery twice – a tendon repair in 1995 and a radio-frequency thermal

capsule shrinkage in 1999 – and his career becomes even more amazing. Unlike

pitchers of the past that were injured, lost velocity, and had to either learn

to pitch on guile or sell insurance in their hometown, Schilling remained a

power pitcher.

Much of the story of Schilling’s season and certainly his

post-season heroics will be based around the ankle. First, we must know the

injury that Schilling was combating. Often described as an ankle sprain or a

torn tendon, neither is medically correct. Get ready for the big words. The

retinaculum, one of seven in the ankle, is nothing more than a thickening of a

fascia designed to hold tendons in place inside a shallow groove. As a point of

reference, the retinacula run perpendicular to the bony ‘bumps’ of your ankle.

The primary function for a pitcher would be the dorsiflexion

(movement of the foot up, toward the shin) as this is the action that would

occur during the wind-up stage of the pitching motion prior to the push off.

The other significant structure that goes beneath the retinaculum is the

superficial peroneal nerve. If the retinaculum were to be damaged to such a

point as to allow the tendon beneath to exit the groove through which they pass,

the movement in and out of the groove would put pressure on this nerve, causing

the majority of the pain felt with this injury.

Given this injury, we must now pinpoint where the injury

occurred. It appears that the injury first manifested itself on May 13th

during a start at Toronto. Video of the game is inconclusive, but sources have

indicated that Schilling injured himself on a fielding play. This is consistent

not only with the symptoms but the later escalation of the injury in October.

The injury does not appear to affect Schilling’s pitching motion significantly

and where it did, the medical care he received from the Red Sox medical staff

certainly appears to have been effective. During the season, Schilling showed

little or no indication of injury effects. His stats are remarkably consistent

both before and after the injury.

The Red Sox initially tried to cover the severity of the injury.

This is typical for most baseball teams. As late as June, the Red Sox were still

insisting that Schilling had nothing more than a bone bruise. Schilling was

already receiving injections of marcaine, a pain deadening agent, both before

and during games. The Red Sox medical staff was making a calculated risk

that they could keep Schilling at a functional level without increasing the risk

of exacerbating the injury. By deadening the ankle, Schilling could not tell if

he was doing further damage. Each pitch was another roll of the dice that he

would not rupture a necessary structure.

Schilling’s injury came at almost exactly the twenty-five

percent mark of his season. His strikeout numbers dropped slightly, from seven

strikeouts per start before the injury to six while his walks ticked up

slightly, from one per start to 1.1. Schilling was able to pitch enough to rank

third in innings, second in ERA, third in strikeouts, fourth in batting average

against, and first in wins. Hurt, he was better than almost every other pitcher

in the American League. It is hard to say that he could have been any better if

healthy.

Given his results, the injury cannot be considered in relation

to his regular season. There is no evidence that normal medical care did not

return Schilling to full function. Where the story changes is the playoffs.

Schilling came off the mound during his start in the ALDS, against the Anaheim

Angels, and slowed when he realized he would not need to cover first. Video

shows that he was running forward, from the mound to the dugout, his head turned

to his left to watch the play when he stepped on the edge of the grass at the

first base line. His ankle buckled under him and Schilling hobbled back to the

dugout. While it did not look especially significant, all indications are that

his previously weakened retinaculum ruptured at this point. The gamble that the

Red Sox had taken all season long finally came up snake eyes.

Schilling came to the mound for Game 1 of the ALCS just as he

had all season. He was hobbled, but felt no pain after his injection. He had

discarded a brace – “too tight”, he said later – but from the first pitch, it

was clear that he couldn’t pitch in this state. He was pulling his foot from the

rubber rather than pushing off. His fastball showed only 86 mph and the results

were predictably ugly. He lasted three innings before leaving the

game. At that point, Schilling’s chances of returning for a Game 6 start were as

bleak as the Red Sox chances of even making it to a Game 6.

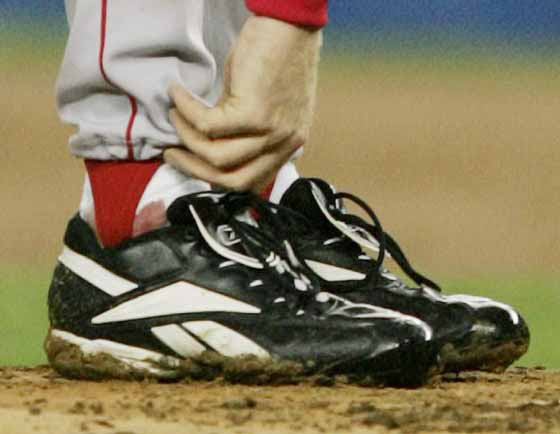

As the Red Sox fought back from a 3 games to none deficit, the

medical staff went to work. The brace discarded, Reebok was asked to design a

supportive shoe. Shown on national TV, the shoe was never a factor. Some suggest

that it was always a red herring, the hightop designed not to support but to

cover. Cover what? Blood.

Dr. Bill Morgan was experimenting with a cadaver to see if he

could hold the tendon in one place, actually dislocated from its normal seat, by

means of a few sutures through the skin. Anchoring to the underlying tissue, the

sutures provided just enough resistance to the tendon’s intended path, but there

was no way to test the stress pitching at this level would place on it.

National TV focused on the ankle as blood seeped through

Schilling’s sock, but the secret sutures below were just able to hold. In the

first procedure before Game 6, three sutures were put in. When Schilling left

the game, his ankle throbbing, only one was left intact. Four sutures were used

in Schilling’s single World Series start, but none were able to hold throughout

this start. The Red Sox acknowledge that Schilling likely could not have

undergone another procedure, meaning he would not have been available for

another start.

Schilling owes his second World Series ring to creative,

competent medical care. His red sock, literally bleeding for the team, has

become a symbol of sacrifice. The myth will always outstrip the truth and in the

telling, it will expand and expound. In this case, the truth is enough. This

triumph certainly needs no exaggeration.